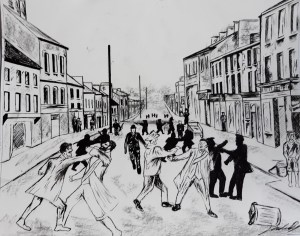

THE RIOT ‘SACKING’ of LISTAMLET, LISTAMLAGHT ON 14 AUGUST 1880 AND ITS AFTERMATH

ANTHONY FOX

The townland of Listamlet also known as Listamlaght which translates from the Irish to ‘the fort of the plague burial’ it consists of an area of 166 acres. It is located two miles from the Moy and one and a half miles from Killyman. In the 1880s in order to get to Killyman from The Moy you had to pass through Listamlet. In 1841 the population was 257 with 48 inhabited houses. In 1851, after the famine, it had a population of 196 with 35 inhabited houses, thus categorizing it as a village. Today in 2020, it has 15 houses. In 1880, dirt roads, thatched cottages, and oil lamps were all a very common scene, with agriculture and linen being the main source of employment in the area. The cars mentioned in the following reports were horse-powered, as vehicles using the internal combustion engine or steam were not yet known in the area.

This article is intended to report on accounts of the little known “riot” or as some called it ” the sacking ” of the village of Listamlet on 14 August 1880 and the subsequent much better-known riot two days later in Dungannon. An attempt will be made in the discussion to relate both events with some much later evidence from statements by other participants.

REPORTS ON THE SACKING OF LISTAMLET

According to constable Thomas Bassett’s court account, an Orange drumming party left the Moy, on its homeward journey to Killyman, at 10 pm. It consisted of about fifty or sixty persons in total and in his words ‘’all of them worse of for the drink’’. Bassett and another nine police followed the party, to keep, or to at least to try to keep order. The first contact the drumming party made was with a local blacksmith Samuel Hugh Barker, who was beaten by them at Listamlet Hill.[1]

‘It appears that a party of Orangemen were returning home about half-past 11 o’clock at night from a drumming expedition, they were guarded by an escort of eight police. On their way, they passed through Listamlaght, which is principally inhabited by Catholics, and as they were going along a shot was fired at them. Then commenced a scene which, perhaps could never have been witnessed in any other civilized country. To use the words of my informant, a gentleman of good position, they simply “sacked” the village. Most of the inhabitants were in bed and quite unprepared for an attack, and but small resistance was offered to the invading party. They smashed the windows, broke the doors and rushing into the cottages, dealing destruction round them, right and left, on all the crockery and other articles easily broken. The police interfered but the wreckers brooked no interference. They turned on the constabulary and beat them, driving them back towards Moy, and dangerously wounding two. As soon as information reached Moy, the Resident Magistrate (Capt L’Estrange) and Sub-Inspector Locke and subsequently Sub –Inspector Webb in command of a party of police arrived with rifles and buckshot and set out on cars to the scene of the outrage. The appearance presented by the village was at once curious and pitiable. In the dark, moonless night the people were gathered on the roadway in groups or were standing in front of their wrecked houses, while the women and children were brought up by fear to a high pitch of excitement. Not content with laying about them and smashing everything breakable they could find, the midnight rioters, to complete the work of destruction, set fire to one of the houses, belonging to a man, Patrick Fox; but the wind not being high, the flames were fortunately extinguished before the cottage was burned down’[2]

MOY PETTY SESSIONS COURT ON THE RIOT AT LISTAMLAGHT

This fortnightly court was held on Wednesday, 8 September by A Harvey, Esq., R.M, and Dr Elliot, R.N. Sub-Inspector M Gavern was present. The principal case before the court was the enquiry into the charges of riot at Listamlaght preferred by the constabulary against John Dobson, Samuel Gates, Dilworth Gilmore, Benjamin Mullah, Thomas Blair, and James Hill. The alleged riot rose out of a row on Listamlaght hill about a mile from the Moy on the return of a Killyman drumming party from the latter town which they visited on Saturday evening the 14th August. The windows of the Roman Catholic houses on the hill were wrecked and a blacksmith named Barclay who interfered with the crowd on their homeward journey was beaten.[3]

Patrick Fox examined by Mr. Dickie –

On Night of the 14th August about the hour of half-past eleven o’clock, he was in his own house at Listamlaght. The first thing he heard was the beating of the drums and then a party came up cursing him-self and the Pope. Immediately before he heard shots fired in the direction of Moy from where the party was coming. The next thing he heard was the breaking of his kitchen window. All his windows were broken by the same party. He heard a shout ‘’here are the police’’ and a strange voice shout ‘’go on boys or I’ll fire’’ to which one of the party replied ‘’Damn your souls you dare not fire as you have no one to read the Riot Act’’. One of them also said ‘’the police had three prisoners made and come and rescue them the people and the police got into a ‘’bustle.’’ Joseph Dobson said to the crowd ‘’go on and do your work right.’’ John Dobson said ‘’we are Killyman boys and we fix them.’’

Stones continued to be thrown and three cheers were given. After this, he found his house on fire. Samuel Gates of Kinnego was one of the drumming party. Evidence was given by other Listamlet residents testifying to the wrecking of the houses and the beating of Hugh Barker.

Wm M’Creely examined by Mr. Dickie –

I live at Listamlet and I recollect the night of the 14th August. I saw the drumming party coming home from the direction of the Moy. My house is near Fox’s house. I saw Joseph Dobson among the drumming party who attacked my house. I heard no shots fired. Stones were thrown through my mother’s house. I knew none of the crowd but Joseph Dobson. He was nearly in front of our door.

Samuel Barker, examined by Mr. Dickie –

I was in Moy on the 14th August and went homewards, to Culkerin [most likely referring to Culkeeran, a townland just outside of the Moy opposite Major’s lane], by Listamlaght. At the latter place near to eleven o’clock at night, I saw a drumming party. I was attacked here but I cannot tell by whom. The police came up and saved me. I waited some time and then went on to the end of Grange Road. One man I believe him to be Gates – at that place looked into my face and said ‘’Hell to your souls come on now.’’ He struck me with a stick and knocked me down. I was kicked when down by four persons. A voice from the crowd said ‘’ that is Barker and he has got enough’’. They left then and went in the direction of the drumming party. I have no doubt, but Gates is the man who assaulted me.

Constable Thomas Bassett examined by Mr. Dickie –

I remember the night a drumming party came into Moy from the direction of Killyman, they remained there until near ten o’clock. When they left, I followed them out the road with nine men. When going through Killyman street the crowd halted, cheered, and cursed the Pope. They appeared to be the worse of drink. I and my men kept some distance behind them. They conducted themselves badly and out of the town they appeared to be wrangling amongst themselves. We followed them as far as Listamlaght. On the way out a man named Hugh Barker passed us and I unsuccessfully tried to make him return fearing he would get into trouble. On the top of Listamlaght hill, I found Barker fighting with three men. They were beating him. I took Barker away and the three men ran down to the drumming party shouting they were attacked. Barker shouted he could beat any man in Killyman.

About fifty of the drumming party returned and tried to force their way past us. We stopped them and done our best to drive them on. A good many of them were stripped and jumping on the road. They appeared to be like mad demons. A number of them appeared to assist in getting them away. At the brow of the hill, I believe I saw Samuel Gates endeavoring to force himself back against the police. In the best of my belief, he is the man. We halted there and I saw Joseph Dobson come up on my right. He was then about a quarter a mile from his own home. He made a remark as to bad work tonight or something to that effect. He passed behind us in the direction of Moy. I heard windows of the houses in Listamlaght broken. I told my men to come on that we would have to act determinedly with them now. I found two panes broken in McCrealy’s house, this was fully three hundred yards from where I saw Dobson, I hurried on and say a great number of people about Fox’s house. I heard the glass smashing. I arrested a man who was in the act of throwing a stone. He shouted to the crowd to save him. I got a blow on the face from a large stone and was stunned and cut. The prisoner got away.

Three others of my men were injured too. I loaded my rifle and shouted I would fire on them if they did not desist. Someone say we dare not fire. I gave the men in charge of another constable who was there being myself blinded with blood. That man also complained of having been struck on the head with a stone. I sent a man into Moy for assistance. I went over to Joseph Dobson’s house and he was about his own door to the best of my belief. I asked him for a cloth to wipe away the blood and got it and a drink form Dobson himself. I threatened a second time to fire and I believe I would have done so but the night was so dark. I asked Joseph Dobson to use his influence to get the people away. He shouted to the people to be gone from about his place and take away their drums. Then I understood they had put up the drums in the house. I saw parties rushing in for the drums and it appeared to me they all then left. A shot was fired apparently about Fox’s house, ‘’When we came up to Fox’s the attack on his house was going on for some time, I only saw Gates once that night. This was about eleven o’clock at night. Fox’s house was not set on fire until after we left. The people must have returned again and attacked the house a second time.’[4]

The cases against, Dilworth Gilmore, Thomas Blair, and James Hill were stuck out.

Joseph Dobson (Listamlet), Samuel Gates, (from Killyman) and Benjamin Malagh (from Seyloran) were remanded for trial, and at a later appearance were found not guilty.[5] Compensation was separately awarded for some of the properties damaged or destroyed

THE LADY’S DAY RIOT IN DUNGANNON

‘Two days later on August 16 in Dungannon, on ‘’Lady’s Day’’ ’Catholics, headed by a band and carrying a banner, marched from the rendevouz to the railway station, where they joined several other contingents which arrived by train, with bands and banners, some bearing green costumes, and others merely green sashes, emblazoned with the significant crest of a bloody hand.[6] The combined parties marched through a back street leading from the station to the Protestant quarter. Passing along their route without molestation, they wheeled into the main street of the neighbourhood in which they then were – Church Street – and marched through it into the Market Square, from whence, with music still playing lively airs, the processionists moved through the town, and afterwards to Donaghmore Field, a place some miles distant from Dungannon. In the evening, about four o’clock, they returned, the main body advancing through Irish Street, which, it should be explained, forms a continuation with Church Street, the lower end of the square intervening, and a somewhat less numerous contingent through Scotch Street, which leads from the central portion of the lower end of the square, and is at right angles to the two former roads. A party of police numbering thirty, under command of Mr. Ryan, R.M., and Sub-Inspector John M’Govern, of Mohill, were stationed across the entrance to Church Street, as if with the intention of preventing the procession taking that line of route.’[7]

‘However, as the processionist advanced, the line of police drew to one side and allowed them to pass. All the party, however, did not march forward, a large body remaining in Irish street and other portions of the Catholic quarter. The police at Church Street, thinking the whole procession had passed, followed pretty close upon the rear, so as to prevent any disturbance that might arise from a collision between the two factions, and also to guard against the possibility of an attack being made upon the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, situated farther down the street. For a few minutes, it seemed as if all we’re about to pass off peaceably when suddenly a scene of dire confusion ensued. So far as can be gathered from a careful sifting of various accounts, it appears that the procession was marching gaily by, flaunting their banners, one of which bore the names of the heroic achievements formerly inscribed upon the colours of the Irish Brigade, and playing enlivening national airs, when one of some half dozen Orangemen that had collected on the pavements rushed forward and endeavored to burst in the head of the big drum. At once he was set upon by the bandsmen, and several of his comrades running to his assistance, in another second there was a general melee, although, as might be imagined, no doubt could exist as to which side would be victorious. Not satisfied with protecting themselves and their property, the Catholics commenced to smash the glass in the windows in the houses in the street, and for some time the greatest consternation prevailed. As many of the inhabitants as could hurriedly put up their shutters, for many remembered the “sack of Listamlaght’’ and feared that it was about to be indiscriminately avenged by mob violence’[8]

By letting the Moy contingent down Church Street on their own, with the sacking of Listamlet fresh in their minds, a clash with Church Street inhabitants and others, started the disturbances off, with police and more rioters coming up in the rear, the group would eventually make its way back up Church Street and converge with rioters from Scotch Street and Irish Street, with the final stage in the Market Square, ending with the shooting of William O’Rourke.

‘Under the command of Sub Inspector Webb, near the corner of Church Street and the square. Suddenly perceiving a rush of the crowd into the lower end of Church Street, Sub-Inspector Webb ran round the corner, and, finding a large number of processionists beating a man whom they had surrounded, endeavoured, with a few of his men armed with batons, to rescue him. Immediately the mob commenced to fling stones at the police, the missiles coming in showers A large and excited crowd were by this time seen advancing from Irish street, while another equally large body of processionists were observed rapidly moving up the ascent of Scotch Street into the lower end of the square, all animated by the one design. The assembled contingents helped their comrades in stoning the police. Sub-Inspector Webb having without avail called on the people to disperse ordered his men to fix bayonets and charge, but the mob merely retreated a short distance so as to avoid the gathering line of steel, while remaining sufficiently near for their stones to take effect. By this time, the police had been drawn nearer the corner of the square, but the stones and shots continued to be fired, and the sub-inspector was repeatedly struck. Mr. Ryan ordered the police to again charge the mob with the bayonet, but it failed to disperse them. Indeed, the charge seemed rather to irritate than alarm, for many rushed desperately amongst the points of the bayonets. Mr Ryan then read the Riot Act and again called on the people to disperse. They replied by a volley of stones, and then he gave the order to fire. The police loaded with buckshot and fired six or seven rounds. The mob retired a little down Irish Street but rushed back, and the constabulary then fired about a dozen shots, but without deterring the rioters. The police again fired on them, taking aim at the three great divisions of the people – those in the square, in Irish street, and in Scotch street. William O’Rourke, who was killed, was standing among the party at the corner of the square and Thomas Street, which runs parallel to but higher up the square than Irish street and was struck by a bullet in the thigh. He ran backwards about twenty yards and then fell. Evidently, at length cowed by the determined attitude of the police, the mob began to cease throwing stones, upon which Sub-Inspector Webb ordered his men to stop firing. The people then began to disperse, and the riot had practically ended’.[9]

THE INQUEST

An inquest into William O’Rourke’s death was held, he had lived in the townland of Creenagh, just four miles from Dungannon, three of William O’Rourke’s daughters were present,[10]another misfortune that came out was Mrs O’Rourke, unfortunately, had just lost a baby,[11] his son was away annual training, with the Royal Tyrone Fusiliers.[12] Police and civilian witnesses, a Doctor Thomas Browne and Doctor Twigg, who attended William at the time after the shooting were questioned by the coroner a Dr Hamilton from Cookstown. They had both, along with a Doctor McParland representing the family, conducted the postmortem. Police and other witnesses also gave accounts of the day’s events.

Charles Buchan and a John McCann testified to seeing shots coming from Simpson’s house before his windows were broken.[13] At a later hearing, a James Eccles gave a similar account [14]. Eliza McAleary a servant of John Simpson’s tells the court she witnessed Simpson go upstairs with his gun and say that ‘’the first man who would throw a stone at his house he would blow his brains out’’. After hearing 5 or 6 shots within about ten or fifteen minutes he came down the stairs saying ‘’is he dead yet’’.[15]

The jury found that William O’Rourke came by his death, from a gunshot wound inflicted in the right groin on the evening of 16th inst, but by whom the wound was inflicted they were not in a position to say. The jury stated that ” we wish to condemn in the most emphatic manner the practice of drumming parties or processions of all denominations coming into or through the town and hope that such steps will be taken as will prevent a recurrence of this in future’’.[16]However, three men John Smith, Charles Hagan and Joseph McGurk were sentenced to two months imprisonment, with hard labour for rioting.[17]

The dominant musical accompaniment to Orange parades during the 1870s and 1880s was the drumming parties. These drumming parties were looked down upon by respectable classes and by the early 1880s, there was a shift away from slow-moving unmelodic and rough drumming parties, towards flute and brass bands.[18] It would have been common practice for drumming parties during the days surrounding the Twelfth to go to and fro from Killyman to the Moy.

On the evening of the inquest, ‘about eleven o’clock tonight as two policemen were passing through Irish street, four shots were fired at them from a corner house. Immediately the alarm was given at the barracks about a hundred men turned out and remained on guard in Irish street for a considerable time, but as no further firing took place a number of them returned to quarters. At the present moment, armed pickets are as they were last night stationed at the corners of the streets, while the footpaths of the square are almost completely lined with constabulary lying on the flags. Lest it be found necessary to require additional assistance to maintain the peace, a picket of the Mid Ulster Artillery under the command of Lieutenant Brown was in readiness till a late hour to turn out whenever called upon’[19]

THE AFTERMATH (AND ALSO FOR TOM CLARKE)

The consequences of the sack of Listamlet did not finish there. The tradition of the O’Rourke family was that Owen O’Rourke, William’s son, a member of the Royal Tyrone Fusiliers, sought the person who killed his father. He believed from the evidence in court that it was Simpson, who due to bad feeling throughout Dungannon and surrounding areas regarding William’s killing, fled to America with Owen in pursuit. Allegedly Owen attempted to follow him over a river crossing and was killed in America.[20]

Gerard MacAtasney’s book outlines that

‘Tom Clarke joined the I.R.B. in Dungannon, fled to America because of the attack on the police in the town, was sent to London on a bombing mission and spent almost sixteen years in prison. On his release from prison, he married the niece of prominent Fenian, John Daly and was pre-eminent amongst those who sought to initiate a military rising against British rule in Ireland.’[21]

The catalyst for his departure being an attack by Orange supporters on a Catholic parade.[22]

Tom Clarke was the son of James and Mary, his father a Protestant from Leitrim, his mother a Catholic from Tipperary. James Clarke joined the British army in 1847 during the height of the famine. He saw action in Crimea and after returning from this campaign in 1856 he was stationed in Clonmel, County Tipperary where he met and married Mary Palmer. Thomas James Clarke was born the following May, one of four siblings, and was baptized a Catholic. James after seeing service in Africa was appointed Sergeant of the Ulster Militia based in Charlemont fort and eventually moved to Dungannon wherein 1868 he claimed his discharge from the Royal Regiment of Artillery.

Meanwhile, Tom Clarke was already attending St Patrick’s National School in Dungannon and was eventually appointed a teaching assistant in the school. It was during this time that he took an interest in Irish history. It was after an appearance in 1878 in Dungannon by veteran Fenian John Daly that eventually led Clarke and his friend Billy Kelly to join the I.R.B. (The Irish Republican Brotherhood). They would go on to form an I.R.B. circle of twenty-three men in Dungannon.

After the riot, Tom Clarke fled to New York and joined Clan na Gael, the leading republican organisation in Irish America where he volunteered to join its bombing campaign in England. He was arrested in London in 1883 and eventually sentenced to penal servitude for life. He spent fifteen years in jail[23] and after his release, he married Kathleen Daly niece of his mentor John Daly and they moved back to America in 1902 but returned to Dublin in 1907. There, he set about to reform the dying I.R.B. A Military Council was set up in 1915 and along with the Irish Volunteers heavily infiltrated the Easter Rising in 1916. Clarke was court marshalled and found guilty of his role in the Rising and was executed by firing squad on 3 May 1916.[24]

Tom Clarke and Dungannon Fenian, Billy Kelly, often referred to as Willie John Snr both went on the run to America,[25]In his 1948 witness statement to the Bureau of Military History, Willie John gave his account of the Dungannon riot and later shooting by the I.R.B at the police.

‘On the 15th of August 1880, a parade of Ancient Order of Hibernians took place in Dungannon which led to a clash with hostile Orange section of the population. A riot broke out the R.I.C arrived on the scene of the riot about a hundred strong, a magistrate read the Riot Act, and the police opened fire on the Hibernians. A man named Hogan[26] [O’Rourke] was shot dead and several wounded including a brother of mine. On the night of the 16th August 1880, 11 of the R.I.C were ambushed in Irish Street Dungannon by members of the I.R.B including Tom Clarke and myself- about five or six in all. We opened fire on the police, and they escaped into a public house in Anne St’[27]

According to Helen Litton, ‘The lady day riot was a defining moment in Thomas J Clarke, life’[28]

Direct linkage of the sacking of Listamlet, where there was an A.O.H. Hall, and the subsequent Lady Day riot has already been indicated by a recent publication: –

‘On the evening of Saturday 14 August 1880, the Lady’s Day (15th August: the Catholic feast day of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary), a Protestant drumming party marched from Moy to the small outlying village of Listamlet, about a mile out of Moy, where there was an A.O.H hall and band. The party of about 50 had already consumed a substantial amount of alcohol, and threats had already been made in Moy about what they would do to the ‘Fenians’ at Listamlet. As a result, they were followed by some local R.I.C men attempting to prevent a nasty sectarian situation. Unfortunately, the constabulary was ineffective, and there were injuries (including some to the police), damage to property and one house was set on fire. It is thought that this incident, which was reported by word of mouth on Monday’s A.O.H parade in Dungannon, may have contributed to the very serious rioting which occurred in the town resulting in one fatality, many injuries and substantial damage. The rioting was reported to have started when the Moy band and supporters were attempting to go home down Church Street.[29]

This article, primarily based upon the informative local newspaper The Tyrone Courier, supplements the two excellent extensive reports of the Lady Day Riot by Michael McLoughlin[30] [31] with new information that the fatal gunshot came from a local house, rather than from the police fire as indicated in other contemporary newspapers. The witness statement 68 years after the 1880 riot from Billy Kelly indeed also gives fuller insight into the dynamics of the Lady Day Riot and in particular its aftermath.

WHAT IF?

From the dawn of time “What If?” has been in play in the human psyche. The Domino Effect as it is sometimes called is where one event causes a sequence of events that cascade into history being made. What if, the forbidden fruit wasn’t eaten? What if, the Titanic had left on its designated day?[32] What if an 18-year-old aspiring professional painter named Adolf had not had his dreams ruined because he failed the entrance exam of the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna in 1907 and again in 1908? What if Theresa May had not ignored all her advisers and called her fateful General Election of 8 June 2017?

What if Listamlet had not been sacked on 14 August 1880? Would Tom Clarke 36 years later have gone on to be the military strategist for the Easter Rising of 1916? What if, he had not gone on the run to America and not served jail time as a felon? No one can tell how his life would have turned out. He may have simply stayed in Dungannon and continued with his teaching, a very noble vocation I might add. However, in all likelihood, he was always destined for something else. The irony is not lost that both Clarke and Simpson went on the run, albeit forced out for different reasons, but with resultant domino consequences, the starting point of which being the same, the sacking of Listamlet I am indebted to the staff of Libraries NI in the Irish and Local Studies Library Armagh and the Irish and Local Studies Library Omagh. In particular, Christine Johnston has been most helpful in providing me with key reference material from the Tyrone Courier during the COVID lockdown. Assistance and guidance has also been provided by Brian Gilmore in putting together this article.

P.S To end on a lighter note a Bram Stoker mystery Cursed in the Act by Raymond Buckland mentions the sacking of Listamlet

The Morning Herald had published a report of last evening’s events with the bold caption ‘Mysterious Intruder Attempts to Kill American Actor’s Manager Happily’- as I pointed out to my boss- it appeared on page three rather than the front page, being displaced by a lenghty report from Dungannon, Ireland, about a continuation of riots in the Catholic village of Listamlaght brought about by a party of Orangemen. The description of the breaking of windows and doors in Listamlaght, along with the frightening and beating of villagers and the setting on fire of one of the cottages, took pride of place over a falling lighting London theatre.

Irish Times Lady day in the North The Dungannon Riot August 18th 1880

Tyrone Courier Sack of Listamlet

[1] Tyrone Courier, 11 September 1880

[2] Irish Times, 18 August 1880

[3] Tyrone Courier, 11 September 1880

[4] Tyrone Courier, 11 September 1880

[5] Tyrone Courier, 11 December 1880

[6] Lady’s day was normally celebrated on the 15th of August and was a Catholic feast or holy day. It was selected as a day of celebration by a number of political and social organisations especially The Ancient Order of Hibernians who had a significant membership in Ulster at that time. However, in this year it fell on a Sunday, so the non-religious celebrations were held on Monday the 16th

[7] Irish Times, 18 August 1880

[8] Irish Times, 18 August 1880

[9] Irish Times, 18 August 1880

[10] Belfast Morning News, 18 August 1880

[11] The Morning Post, 18 August 1880

[12] Belfast Morning News, 18 August 1880

[13] Tyrone Courier, 21 August 1880

[14] Tyrone Courier, 11 September 1880

[15] Tyrone Courier, 11 September 1880

[16] The Freemans Journal, 19 August 1880

[17] Irish Times, 18 August 1880

[18] Dominic Bryan, Orange parades: the politics of ritual, tradition, and control (London, 2000), p. 48.

[19] Irish Times, 18 August 1880

[20] O’Rourke oral family tradition

[21] Gerard MacAtasney, Tom Clarke Life, Liberty, Revolution, (Kildare 2013) [preface]

[22] Gerard MacAtasney, Tom Clarke Life Liberty, Revolution, (Kildare 2013) page 104

[23] Thomas James Clarke, Glimpses of an Irish Felon’s Prison Life (Cork, 1922).

[24] Gerard MacAtasney, Tom Clarke Life, Liberty, Revolution, (Kildare, 2013) pages 3-105, see also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Clarke_(Irish_republican)

[25] Bertie Foley, William John Kelly – A Fenian; in Dúiche Néill 23, (Monaghan 2016) page 202

[26] Willie John Kelly clearly got the deceased O’Rourke’s surname wrong from 68 years earlier.

[27] http://www.militaryarchives.ie/collections/online-collections/bureau-of-military-history-1913-1921/reels/bmh/BMH.WS0226.pdf

[28] Helen Litton, Thomas Clarke 16 Lives (Dublin, 2014), page 24, see also

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Clarke_(Irish_republican)

[29] James Kane, ‘’Your Lordships Estate’’, A General History of The Moy and Charlemont), (Monaghan, 2014), page 122

Michael McLoughlin, ‘Dungannon 1880 – A Memorable Year’ in Dúiche Néill 21 (2013), pp 132-144.

Michael McLoughlin, A Divided If Not A Foolish People? (Monaghan, 2019) pp 247-253.

The Titanic’s launch was delayed by six weeks because her sister ship Olympic needed repairs in the same dry dock. That delay put seasonal icebergs right in the Titanic’s path. https://eu.jsonline.com/story/entertainment/2017/12/19/100-unsinkable-facts-titanic/964485001/

Pingback: Sack of Listamlet | Listamlet ,Listamlaght

It is mentioned in the House of Commons, that in 1880 Tyrone had a population of 215,000 ,120,000 are Catholic ,and out of the total 120 Tyrone magistrates none are Catholic

LikeLike

Patrick Fox died 3 years later aged 43, on January 8th 1883 ,leaving behind a Wife, Eliza Jane , two children Ellen aged 5 and Daniel age 4 and according to his late Grandson ,Brendan McGrath,Daniel later joined the I.R.B

LikeLike

It was told to me by wee Peter McKearney of Dree,that if people of Listamlet knew there was going to be trouble,with the Orangemen coming through,they would have left there homes,and slept in a drain out towards Grange Park ,

LikeLike

Pingback: An insight into the Riot /Sack at Listamlet ,Listamlaght and the later consequences | Listamlet ,Listamlaght | Listamlet ,Listamlaght

A small piece from the Irish Times into the sacking “Lady day in the North The Dungannon Riot (Wednesday 18th

August,1880 )

From our reporter Dungannon ,Tuesday

All is quiet today in Dungannon.From morning till evening nothing has occurred to interrupt the ordinary

quietude of the town and were it not for the broken windows ,shot and bullet marked walls and parties

of constabulary continually passing through the streets or on guard in the market square nothing would

remind one of the scene of riot and bloodshed yesterday enacted in this town. Business is resumed and

looking on the peaceful picture of provincial life ,the change that within a few hours has come over the

state of affairs seems as extraordinary as it undoubtedly is pleasing .Before describing the riot of

yesterday it may perhaps be of interest to relate an extraordinary occurrence which took place on

Saturday last at a little village in the townland of Listamlaght ,which may ,perhaps throw some light on

the events of yesterday .It appears that a party of Orangemen where returning home about half past 11

o’clock at night from a drumming expedition ,They were guarded by an escort of eight police .On their

way they passed through Listamlaght ,which is principally in-habited by Catholics ,and as they were

going along a shot was fired at them .Then commenced a scene which ,perhaps could never have been

witnessed in any other civilized country .To use the words of my informant ,a gentleman of good

position ,they simply “sacked” the village .Most of the inhabitants were in bed and quite unprepared for

an attack ,and but small resistance was offered to the invading party ,They smashed the windows broke

the doors and rushing into the cottages ,dealt destruction round them ,right and left ,on all the crockery

and other articles easily broken .The police interfered but the wreckers brooked no interference .They

turned on the constabulary and beat them ,driving them back towards Moy ,and dangerously wounding

two .as soon as information reached Moy ,the Resident Magistrate (Capt L’Estrange) and Sub-Inspector

Locke and subsequently Sub –Inspector Webb in command of a party of police arrived with rifles and

buckshot and set out on cars to the scene of the outrage .The Orangemen were,however gone when the

constabulary arrived .The appearance presented by the village was at once curious and pitiable .In the

dark ,moonless night the people were gathered on the roadway in groups ,or were standing in front of

their wrecked houses ,while the women and children were wrought up by fear to a high pitch of

excitement .Not content with laying about ,them and smashing everything breakable they could find

,the midnight rioters ,to complete the work of destruction ,set fire to one of the houses ,belonging to a

man Patrick Fox ;but the wind not being high ,the flames were fortunately extinguished before the

cottage was burned down .The only arrests made in connection with the affair are those of two men

named Dobson ,both residents of the village of Killyman .They were brought before Dr Elliott RM Moy

yesterday ,Capt L’Estrange being absent in command of a party of Police at Benburb near Moy .They

were remanded .By some it is supposed that the disturbance of yesterday was in retaliation for the

attack on the village . rest can be read here https://listamlet.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/lady-day-in-the-north-the-dungannon-riot-august-18th-1880.pdf

LikeLike